-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Fabian Renger* and Attila Czirfusz

Corresponding Author: Fabian Renger, Medical Care Centre Dr Renger/Dr Becker, Heidenheim, Germany.

Received: April 1, 2022 ; Revised: April 16, 2022 ; Accepted: April 19, 2022 ; Available Online: April 30, 2022

Citation: Renger F & Czirfusz A. (2022) Marketing, Public Relations and Aspects of Investment in The Medical Care Centre in Germany. J Nurs Midwifery Res, 1(1): 1-8.

Copyrights: ©2022 Renger F & Czirfusz A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Abstract

Introduction: In Germany, medical care centres are a focal point in considerations of processes in the area of medical economics.

Objectives: Aspects of marketing, but also other business areas gain in importance.

Methodology: Recommendations for action for medical care centres are to be derived on the basis of research into scientific articles and careful analysis of the facts.

Results: New fields open up regarding know-how relating to medical care centres.

Conclusions: Optimisation processes can only be designed by means of knowledge of the interrelationships.

Keywords: Medical care centers, Public relations, Investments, Marketing, Practice logo, Practice website

INTRODUCTION

Marketing in The Medical Care Centre (Mcc)

While the concept of the ‘medical care centre’ has been in existence since 2003 and the Polikliniken (multi-disciplinary outpatient clinics) of the former GDR were comparable to them, it is only in recent years that MCCs have picked up momentum. In this context, a relatively new development is the founding of MCCs that consist of only one discipline, e.g. dentists. “There are many reasons to set up an MCC and therefore only the marketing for MCCs will be discussed here” [1]. Marketing for MCCs displays a range of special features. These are the result of the owner structure, the number of different sites, the types of medical services provided and the employment status of the service providers (doctors). With regard to the owner structure of MCCs, a number of variants can be observed. These include hospital-run MCCs, collectively organised MCCs, externally financed MCCs and owner-operated MCCs - as well as a large number of mixed variants.

Marketing for hospital- or clinic-run MCCs

Marketing for MCCs run by hospitals or clinics often presents a particular difficulty: on the one hand, sufficient patients need to be attracted for the MCC, and on the other, the referring doctors or specialists in the area surrounding the hospital or clinic must not be antagonised. A tightrope act. However, it is possible to find a solution here.

One of the simpler versions for reconciling these two concerns is to set up a separate area for the referring doctors or specialists on the MCC website. Here, space is given to medical specialisations and the available referring physicians are named. This can be implemented by means of ‘virtual expert consultation hours’, where experts discuss via internet, for example [2].

Marketing for MCCs in relation to the personnel structure

The advantage of an MCC is that any number of doctors/dentists can be employed. The disadvantage is that this leads to relatively high personnel fluctuations in a considerable amount of MCCs. Marketing for MCCs needs to take these constraints into account. If the MCC is not owner-operated, marketing for the MCC should not be based on the (predominantly) employed doctors, but instead on the name of the site and the type of medical services available. This prevents an excessive loss of patients when one of the practitioners departs from the MCC and in the worst case sets up a practice in the immediate vicinity of the MCC [3].

Marketing for MCCs in relation to the sites

The issue of the site is of particular importance in marketing for MCCs and can be differentiated as follows:

The correct marketing approach is derived on the basis of the current situation of the MCCs [1].

Tips for successful practice marketing

The patients not only need to receive medical treatment, they must also feel that they are in good hands and given optimal care. The background for successful practice marketing is depicted below in bullet-point format:

OBJECTIVES

The Medical Practice Logo: Design Proves Effective

Some logos are recognised by every child. Companies such as Apple, BMW or Nike are identified on the basis of the logos worldwide - even without the corresponding lettering. Just seeing the apple with a bite taken out of it on smartphones or computers triggers specific thoughts and feelings. This fact proves the importance of having a meaningful and memorable logo that represents the respective medical practice. If the logo is recognised everywhere, the brand is a success - whether the brand is a sporting goods manufacturer or a medical facility. The logo of the medical practice is therefore an important component of successful practice marketing [1].

The logo of the medical practice as a key component of the corporate design

Modern medical practices need a credible and appealing corporate design. The aim is to attract the attention of potential patients and create a lasting impression. Most importantly, the design of the website, which often constitutes the first point of contact between patient and practice, should convey as much information, personality and competence as possible. Ideally, the logo will reflect the character of the medical practice. The logo selected should be highly recognisable and evoke positive associations. The new logo should, of course, appeal to the practice owners - however, it is very important for the practice to have a distinct presence and that patients feel that the logo is aimed at them. Decisive factors in selecting the logo are:

When it comes to the medical practice logo: less is more

Depending on the alignment and the target patient group, the logo of the medical practice can be fanciful or serious, classic or modern, colourful or monotone. The general rule is that simpler logos are more likely to be recognised. The most successful logos can be drawn with a few brush strokes - and this is what makes them so memorable. In the healthcare sector in particular, graphic designers often make use of plain shapes, structures and colours. The basic approach is ‘less is more’. If the aim is to convey multiple messages, it is often difficult to focus, and the logo soon starts to contain too many elements. In such cases, a balance is often struck in order to present the results. The logo generally contains the name of the medical practice and a graphic sign or symbol, referred to as the ‘key visual’. The result is a combined word-and-image logo that people can identify instantly and that stands for expert treatment and high-quality services. The font and colour form the basis of the brand identity. It is displayed on the website, on the practice clothing and in written communication. The logo is the essence of the corporate design and should create a lasting impression [5].

Recognisable, unique, original

To have long-term success on the market, the practice must be present as a brand and have positive connotations. The design of the logo must comply with this objective. An original and unique logo creates a lasting impression. The graphic designers at the advertising agency develop a consistent design concept for the practice, beginning with the logo and running through all areas of the practice’s external communication. This includes signage, printed material, stamps, advertisements and, of course, the practice website. The cornerstone of all these design components is the new logo. The medical practice will stand out from the competition clearly and unmistakably - patients will be able to associate the practice with a clear statement. An appealing design on medical forms, folders for offers, information brochures for special services, and posters for the waiting room leaves patients with a positive feeling and is generally perceived to stand for professionalism, reliability and a healthy financial footing [5].

RESULTS

Practice Website

Many people look for a doctor online. The only way to be found quickly is with an individual website that is displayed optimally on all devices (responsive web design). If the practice presents itself in an informative way, this creates appeal and trust.Having a website for the practice can thus help to bring in new patients and increase brand awareness. A website should always comply with the latest technical standards and the legal guidelines and requirements [5].

METHODOLOGY

Tax Related Issues

According to section 95(1) book V of the German Social Code (SGB), MCCs can participate in statutory health insurance (SHI) healthcare. MCCs are multidisciplinary facilities run by doctors, involving doctors working as employees or SHI-accredited physicians. They can make use of all permitted organisational forms [6-14]. Limitations in the selection of legal form may, however, arise on the basis of SHI-accredited physician law or healthcare profession chamber legislation in some federal states.

Founding an MCC

All service providers can be shareholders if they are involved in medical care on the basis of approval, authorisation or contract. This will primarily involve doctors, as MCCs need to be doctor-run facilities. Regardless of whether the MCC is run in the form of a partnership company or a corporation, the shareholders involved in its founding are able to contribute their practice or their share of a practice. In terms of income tax, these are transactions considered similar to sale or exchange processes that trigger the realisation of profit. To configure this process to be as tax-neutral as possible, any profit should be subject to beneficial tax rates and create additional depreciable volumes.

Contributing an individual practice

If the founders decide to contribute their individual practices to an MCC organised as a partnership company, section 24 of the Reorganisation Tax Act (UmwStG) applies. The legal consequence of the contribution is that the business assets that are contributed can be carried at their carrying amount, the greater going concern value or an intermediate value.

If the contribution is performed on the basis of carrying amounts, this can be done in a tax-neutral way. If a shareholder receives, in addition to their partner share in the MCC, an additional payment that does not become part of the business assets, this constitutes a taxable sale. The valuation option then only applies to the share of the contributed assets that are not considered sold [15].

If, on the other hand, all hidden reserves are realised, i.e. incorporated at the higher going-concern value, the exemption and the one-fifth rule pursuant to sections 16(4), 34 German Income Tax Act (EStG), apply to the contribution profit. According to section 24(3) sentence 3 UmwStG, however, the tax concession does not apply if the same persons are involved on the side of the contributing party and on the side of the acquiring MCC. In this case, the contribution profit is to be taxed as current profit. From a tax perspective, contribution at carrying amount is therefore the better option. This is, however, subject to the condition that the previous individual practice owners and the acquiring MCC each compile a balance sheet. After the contribution, a return to cash basis accounting pursuant to section 4(3) German Income Tax Act (EStG) is possible [15].

Contributing a share of a practice

The tax concession pursuant to section 24 UmwStG (see above) also applies to the contributions of shares of group practices to the MCC that are to be run in the legal form of a partnership company. If the MCC is to be organised as a corporation, e.g. as a Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung (private limited liability company, GmbH), both individual practices and shares of group practices can be contributed to a GmbH in the course of the formation by non-cash contribution or - after formation by cash contribution - in the course of non-cash capital increase.

Contribution to a corporation is subject to section 20 UmwStG. The tax concession is subject to the condition that a business, business unit or partner share is contributed to a corporation that is liable to tax without limitation. The contribution in kind must in each case take the form of granting new shares to the receiving company (MCC). The corporation has the option of carrying the contributed business assets at the taxable carrying amount or a higher value (the maximum going-concern value). The value at which the corporation carries the assets is considered the selling price by the contributing party and simultaneously as the acquisition costs of the company shares granted in return. A capital gain by the contributing party receives preferential tax treatment by means of section 20(5) UmwStG according to section 34 EStG if the contributing party is a natural person [15].

Running an MCC

Running an MCC entails tax risks that need to be minimised. Partnership company: Corporations can also participate in MCCs. They generate income from trade/business. Shareholders in an MCC run as a partnership company who work on a freelance basis risk their freelance income being tainted by the trade income and thus being reclassified as also being income from trade/business and therefore liable for trade tax. The liability for trade tax by virtue of legal form also applies to freelance partnerships that a corporation participates in where this corporation’s shareholders and managing directors all work on a freelance basis. Corporation: In the case of contribution to a corporation, the doctor can work in the MCC as an employed doctor or as a managing director without losing the above-mentioned preferential tax treatment if the doctor terminates their professional activity in its previous form and performs the work for the account of the MCC. From the activity as employee or managing director of the MCC, the doctor then receives employment income, which is subject to pay-as-you-earn deductions. In such cases, a tax-optimised salary structure is advisable. This can take the form of a company pension, direct insurance, a company car or reimbursement of travel costs, for example [15]. If a shareholder managing director who has contributed their practice/share of a practice to an MCC run as a corporation treats patients for their own account, there is a risk of hidden distribution of profits. In relation to a corporation, hidden profit distribution refers to an asset reduction that results from the corporate relationship. Accordingly, a hidden profit distribution can take the form of the shareholder managing director taking advantage of business opportunities of the MCC on their own behalf or using the company’s knowledge of business opportunities for their own account. On the other hand, it is not objectionable if the company takes advantage of business opportunities available to it by commissioning its managing director with the task of executing its business as a subcontractor [15].

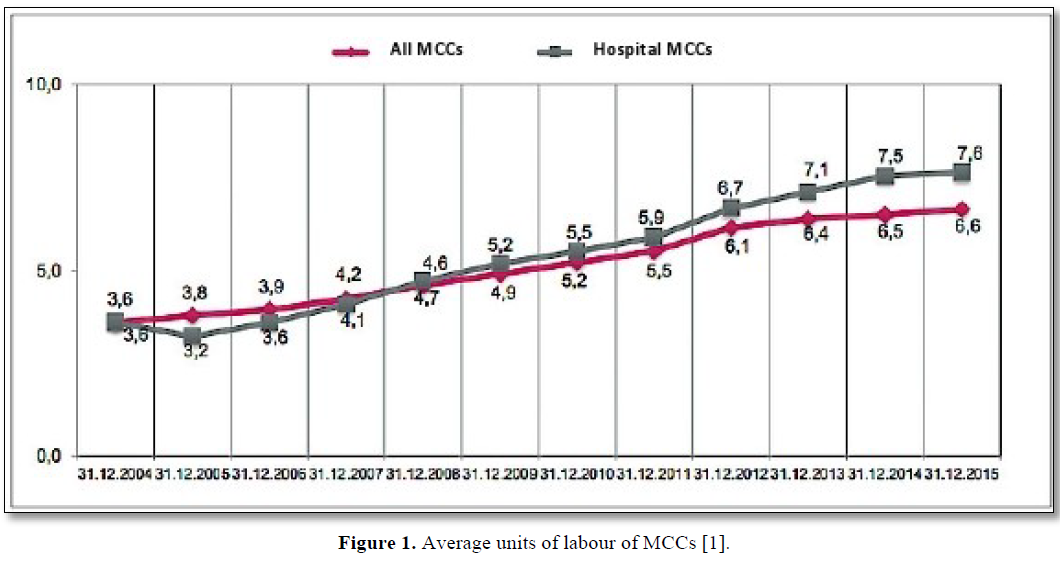

Average units of labour

The average units of labour of an MCC are increasing slowly but steadily. The MCC works with 6.6 doctors on average as at 31 December 2015 (Figure 1).

What does it mean for healthcare if, in addition to doctors, not only hospitals are permitted to act as service providers, either directly or indirectly, but ultimately also non-medical third parties? What steps can be taken to ensure that the quality and availability of healthcare provision is not overwhelmed by capital interests? And would it not be better to establish standards to fundamentally put an end to this development? This was one of the predominant issues in the legislative process for the German Appointment Service and Care Provision Act (TSVG). Key debates were concerned with the issue of whether it was necessary to enact legislation to keep outside capital out of healthcare. But this is no longer possible. Not least because the classic practice takeover, with one ‘medical person’ acquiring the practice from another, in the vast majority of cases requires the raising of capital, up to now mostly in the form of a bank loan[1].

RESULTS

Detrimental Profits In Non-Profit Mccs

As at 31 December 2014, 38% of MCCs were operated by hospitals, with the aim of thus being involved in the outpatient care of SHI patients. Tax-privileged hospitals mostly establish tax-privileged MCCs as non-profits GmbHs (gGmbHs). Because of the funding of social welfare, the profits are not liable for corporation tax or trade tax. A recent amendment to the tax code application decree sets narrow limits for how much profit can be made by non-profit MCCs, however. Excessive profit is fully liable to tax and there is a risk of the non-profit status being withdrawn.

Non-profit status of an MCC

The non-profit status of an MCC calls for compliance with the relevant provisions in sections 51 ff. AO (the German Tax Code). The instruments of incorporation of non-profit MCCs generally state that they support public health, public healthcare and welfare. If the binding requirements for the instruments of incorporation pursuant to section 60 AO or in accordance with the sample instruments of incorporation (annex 1 to section 60 AO) are complied with, the MCC gGmbH is recognised by the tax authorities as having non-profit status [16]. The profits are, however, only exempt from corporation tax or trade tax if the MCC fulfils the requirements for a tax-exempt special-purpose enterprise (sections 65 ff. AO). Otherwise, the MCC would be a taxable commercial undertaking. Further regulations must be observed:

Special-purpose social welfare enterprise pursuant to section 66 AO: Here, the MCC must be able to prove that at least two thirds of its services benefit persons in need of help in accordance with section 53 AO. This is possible in most cases, since the provision of medical treatment for sick people generally applies. Accordingly, it has thus far been possible to treat MCCs as tax-exempt without any major problems (Bavarian State Office for Taxes, BayLfSt 27.11.06, S 0185 - 1 St 31N and Oberfinanzdirektion Frankfurt am Main, OFD Frankfurt a. M. 26.9.06, S 0184 A - 11 - St 53) [16].

Principles of profitability for all MCC operators

For the MCC to be a special-purpose social welfare enterprise, its activities must not be carried out for the purpose of acquisition according to section 66(2) sentence 1 AO. The Federal Finance Court (BFH) has issued a fundamental judgement regarding this requirement (BFH (27.11.13, I R 17/12)). The BFH judged that a facility is run ‘for the purpose of acquisition’ if it aims to make profits that exceed the specific financing requirements of the respective commercial undertaking. Making profits is to a certain extent - e.g. to compensate for inflation or to finance operational maintenance and modernisation measures - acceptable. PRACTICAL NOTE In a letter from the German Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF (26.1.16, IV A 3 - S 0062/15/10006)), the tax code application decree (AEAO) was changed with immediate effect. The fiscal authorities adopted the BFH’s strict interpretation in no. 2 AEAO pursuant to section 66 virtually unchanged. They merely added that profits are also permitted for financing special-purpose social welfare enterprises while the subsidisation of other special-purpose enterprises is deemed harmful [16].

CONCLUSIONS

The Mcc As An Object Of Speculation - What Is The Situation?

According to information from the German National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV), more than 2,800 medical care centres (MCCs) were approved in Germany by the end of 2017, with roughly 18,000 doctors employed or working as freelancers. As the German healthcare market is characterised by strong sales and resilient to economic trends, it is of interest for investors. Accordingly, financial investors are increasingly acting as MCC operators - particularly in radiology and nuclear medicine. Resulting (legal) questions are answered in the following article [17].

MCCs: The Legal Background

In 2004, legislators launched the MCC model in order to create new employment opportunities for doctors in outpatient care and the option of collaboration between different medical disciplines and non-medical service providers. The group of potential MCC founders is currently restricted to doctors and hospitals approved to provide SHI-accredited healthcare, providers of non-medical dialysis services, non-profit operators with a service mandate and communes, in accordance with section 95(1a) Book V of the German Social Welfare Code (SGB V), to ensure that medical decisions remain independent. MCCs that were founded earlier on by other service providers, when this was permitted (e.g. healthcare product providers, care/rehabilitation facilities, pharmacies) enjoy the protection of acquired rights [17]. The founding of an MCC is now only permitted in the legal form of a partnership company (such as a partnership organised under the German Civil Code (a GbR), a partnership), a registered cooperative or a private limited liability company (GmbH), or as a public sector MCC.

Existing founding requirements

Apart from the suitable founder characteristics and the selection of a permitted legal form, at least two half-SHI approvals must be available for an MCC to be founded. In the MCC, a medical director must be active as an employed doctor or an independent SHI-accredited doctor. Collaborative management by doctors from different disciplines is also conceivable. Some areas of management may be run by non-medical staff, for example.

Investment modalities

Private equity companies (investment funds) collect capital and invest it in shareholdings in order to sell them later on at a profit. This therefore involves investing private capital - generally for a limited time period [1].

Companies, such as the medical device manufacturer Siemens, also invest. Because of the strict requirements regarding the permitted legal form, investors are normally prohibited from founding or acquiring MCCs themselves. Nevertheless, an indirect holding can be considered by means of acquiring a clinic involved in SHI healthcare that is permitted to participate in and operate an MCC. Furthermore, freelance doctors can waive their approval for the purpose of being appointed to an MCC and transfer their approval to the MCC. An MCC can thus directly acquire approvals of SHI-accredited GPs. This is subject to the condition that the person handing over their approval continues to work as an employee at the MCC for at least three years. A call for tenders for the transferral of an approval is not required – which also means that the Approvals Committee of the health insurance companies cannot have an allocative function as regards the filling of vacant positions.

In addition, an MCC can, like any other service provider, issue calls for tenders for vacancy approvals and apply for advertised doctors’ positions. Acquired practices can continue to be operated with an employed doctor at the same location. This gives non-medical investors access to outpatient medical care. With the acquired doctors’ positions, it is possible to organise lucrative, highly specialised healthcare (n.a. 2020 Investitionen im MVZ). Private radiologists looking to surrender their practice may be spared a lengthy search for a potential successor given the increasing willingness to invest. There are likely to be many opportunities - depending on the tax advantages and disadvantages - to sell the practice profitably and continue working at financially appealing conditions, possibly with a reduction in working hours and free from the burden of administration in the employment relationship [2].

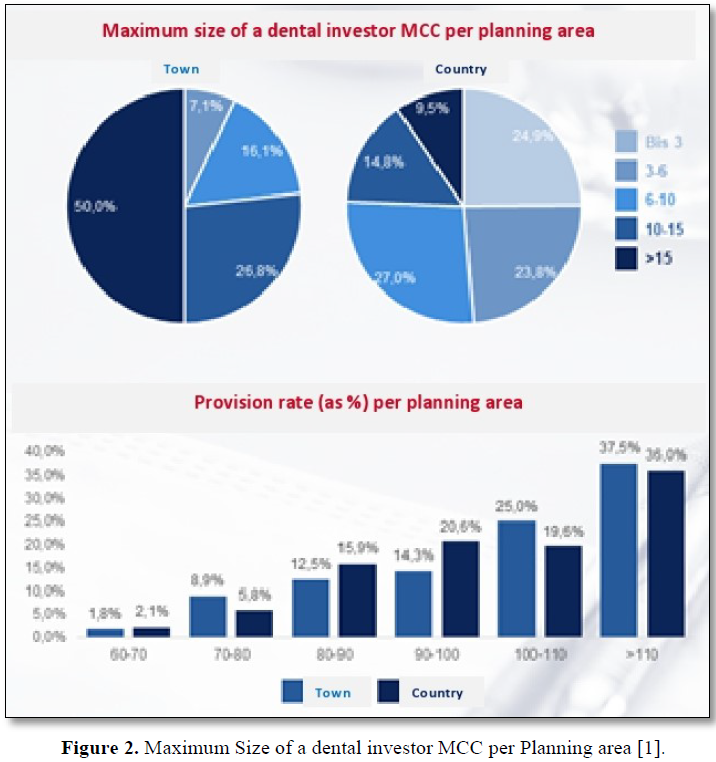

Figures and trends

MCCs are currently becoming a bit of nightmare for many doctors and specialist physicians. The centres often have the backing of investors worth millions and are competing with medical practices, particularly in lucrative city-centre locations. Large-scale and financial investors are entering the high-yield market with their billions. Recently, the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists (KZBV) warned of the ’unimpeded influx of non-medical investors’. KZBV director Dr Wolfgang Esser called on Federal Health Minister Jens Spahn (CDU) to put a stop to the ‘gold-rush mentality’. Franz Knieps is now vigorously opposing this. ‘This distinction regarding where the money is coming from is absurd,’ the chair of the health insurance companies (BKK) said to the Association of Accredited Laboratories in Medicine (AKM). He considers it ‘simply not serious’ that ‘those who earn money in an individual or group practice can pride themselves on doing so […] but others who invest the money institutionally and want returns of 5% are deemed predatory investors.’ Nevertheless, he could imagine that ‘firewalls’ might be needed to keep the numbers of MCC operators and owners with no relation to healthcare low. The same applies if a company develops a dominant position in the market in one area of healthcare. ‘After all, I do not want to be served by just one chain in the entire country.’ Esser thus warned of monopolisation and a worsening in healthcare [18]. The emphasis was clearly more on ‘one’ than on ‘chain’. As Knieps does not accept the contrast between independent practices and investors: he says that investors ‘are often accused, even by politicians, of only being interested in quick profits, draining the market and then disappearing and leaving behind problems with healthcare provision. This is quite a stretch. I would like to see the historical evidence.’ The KZBV had accused investors of having a duplicitous business plan: penetrating the market rapidly, optimising returns on the units that have been bought up and then selling the investments later on with large profits. They said barely any focus was given to supplying healthcare to meet demands or the well-being of patients. These are not long-term investments; the investors are ‘looking for short-term returns’. Approval MCCs in the hands of investors focus especially on high-return areas such as implantology and complicated dental restorations, rather than all-inclusive care [18]. The number of approved MCCs in Germany is increasing constantly, as is the number of hospital-run MCCs. In 2016, the total MCC approvals increased by more than 13%. The vast majority of MCCs work with employed doctors. In 2017, MCCs employed 1,112 specialist doctors for diagnostic radiology and 342 practitioners of nuclear medicine.

Of 2,821 approved MCCs in Germany at the start of 2018, 1,163 (a good 40%) were operated by hospitals. In the Free State of Thuringia, almost three quarters of all MCCs were run by clinics at this time, with SHI-accredited doctors making up barely one fifth of MCC operators. In Brandenburg, Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, hospitals run roughly 60% of all MCCs. The number of medical practice and MCC locations in Germany owned by private equity companies was estimated to be 420 in 2018. In 2017, 35 MCC takeovers involved private investors, and in 2018 the figure was much higher. It is apparently not known how many investor MCCs there currently are in Germany. According to KBV, it is not possible to reliably identify the owners as private equity companies in the medical field. The situation is thus unclear [19].

Misgivings regarding the increase in investors

The concerns expressed regarding the increasing involvement of investors in MCC operator companies are varied.

To stop investment behaviour from getting out of hand, one approach could be to exclusively approve doctors that work at an MCC to be its operator, or at least to guarantee them a majority share. For other MCC operators, such as hospitals, one option could be (to prevent the range of services provided by the hospital from expanding via the MCC) to demand that the services offered by the hospital relate to those of the MCC in terms of the medical discipline or to prescribe a regional relationship, i.e. MCC operation only being permitted within the clinic’s planning area. Exemptions could or should be provided for areas where inadequate provision already is or threatens to become a problem [19].

CONCLUSIONS

Marketing and public relations are of great importance in the MCC. With regard to investment, facts are coming to light revealing that the MCC is increasingly profitable even for non-medical investors. There is no easy way to counter this state of affairs. Of course, attempts can be made to put a stop to developments by means of government legislation. It will not be possible to eliminate this entirely, as even general practitioners, in whatever form, make a profit from their work, even if this is just to keep the practice in operation. It remains to be seen how the healthcare landscape will develop, not only in terms of the MCCs but in terms of all the facilities that exist in Germany.

REFERENCES

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :